Table of Contents

Yemen, Afghanistan, Sudan, and Azerbaijan — all these countries have been or are currently in a state of war for years. However, despite the ongoing conflicts, dozens of civilian aircraft have been taking off and landing from the airports of their capitals, carrying passengers not only to neighboring countries but also to other continents.

Not to mention the two thousand flights per week departing from Israel’s Tel Aviv, which has been in a state of war since 1982 and is constantly under attack.

A contrasting example is Moldova. Although this country is not involved in armed conflicts, its airspace is periodically closed for security reasons.

It turns out that war does not necessarily mean “closing the sky,” and a “closed sky” does not necessarily indicate war. So why are there no civilian flights in the Ukrainian airspace?

Israeli scenario

In April, the European Organization for the Safety of Air Navigation (Eurocontrol) released a forecast indicating that flight restrictions over Ukraine would remain in effect until 2029. Ukrainian authorities disagreed, stating that the airspace would be operational immediately after the end of the war.

A recent visit to Kyiv by the management of the Irish airline Ryanair revived discussions about the possibility of earlier resumption of air travel. The company’s CEO, Michael O’Leary, revealed that Ukraine is working on the potential for a partial reopening of its airspace. If successful, the airline is prepared to launch several flights to Ukrainian cities by the end of 2023. However, opening the airspace at present will be extremely challenging.

According to the director of the consulting company Friendly Avia Support, Oleksandr Lanetskyi, the situation in Ukraine is unique because no other country has ever closed its airspace for 17 months.

“In Syria, Iran, Ethiopia — nowhere in the last 60 years has an aviation blockade lasted more than two months,” he says.

However, he acknowledges that none of these countries had an adversary with the level of weapons possessed by Russians. Moreover, in those countries, air transportation is usually carried out by state-owned airlines using their own aircraft.

Israel could serve as a reference point for Ukraine, but there are two reasons why the Israeli scenario might not work.

The first reason is that the security of Israeli airspace is significantly higher than in Ukraine. Russia possesses a powerful arsenal of weapons, including ballistic missiles with long-range capabilities, which require modern missile defense systems to intercept.

On the other hand, the main threats to flight safety in Israel come from unguided small-sized munitions, which have relatively low power and range of impact, explains aviation expert Bogdan Dolintse. The Iron Dome air defense system is designed to counter precisely such challenges.

Moreover, the Israeli national airline, El Al, is the only company in the world whose civilian aircraft are equipped with special heat traps, similar to those used on military aircraft, says Dolintse.

Source: Airways Magazine

Thanks to these heat trap systems, their aircraft can automatically defend themselves when a missile is detected. Such protection systems on aircraft, along with the Iron Dome, have demonstrated that the country can ensure flight safety at an adequate level. This allowed them to operate regular flights.

The second reason is that Ukraine’s territory is thirty times larger than Israel’s. To cover such an extensive area from hypersonic missiles would require enormous financial resources for the acquisition of air defense and missile defense systems. Currently, Ukraine critically lacks missile defense systems to protect even its largest cities, let alone airports and airspace.

Source: Getty Images

“If we decide to purchase hundreds of air defense and missile defense systems and deploy them at every airport, you can’t even imagine the huge costs involved, with numbers consisting of nine zeros,” theorizes Bogdan Dolintse.

Thus, due to a combination of factors, launching air transportation in Ukraine similar to Israel is impossible.

Can the airspace be opened?

The resumption of civilian passenger and cargo flights will depend on ensuring the safety of passengers and aircraft. Therefore, all risks will be assessed based on the existing weapons in Ukraine, their range of use, and the capabilities of the potential enemy.

These conditions will remain relevant even after the end of the war. The cessation of the state of war does not automatically mean that the airspace becomes safe. Moreover, Ukraine’s own recognition of the airspace safety is insufficient to resume passenger transportation, as it would require convincing international regulators, carriers, and insurance companies.

See also: Shield for Europe: Why the initiative for joint air defense system divided allies

Currently, the complete opening of the airspace for civilian aircraft is not possible, according to experts in the aviation industry. From a technical standpoint, only partial reopening can be considered, such as the operation of specific airports and a limited number of irregular cargo flights. There are two realistic scenarios for Ukraine’s partial airspace unlocking, and they bear some resemblance to the mechanism of the “grain initiative.”

“Green corridors”

Ukraine can independently ensure flight safety by implementing air defense and missile defense systems along specific routes, after which the military and the State Aviation Service can identify safe zones for aircraft movement. This means that flights will be operated through separate corridors, explains Dolintse. However, this approach has several drawbacks.

Firstly, airport capacity is a significant obstacle. The Uzhhorod airport could potentially be included in a “green zone” as it is located close to the border, and after take-off, planes enter Slovakian airspace. However, the capacity of this airport does not allow for the reception of most modern aircraft, including Boeing models.

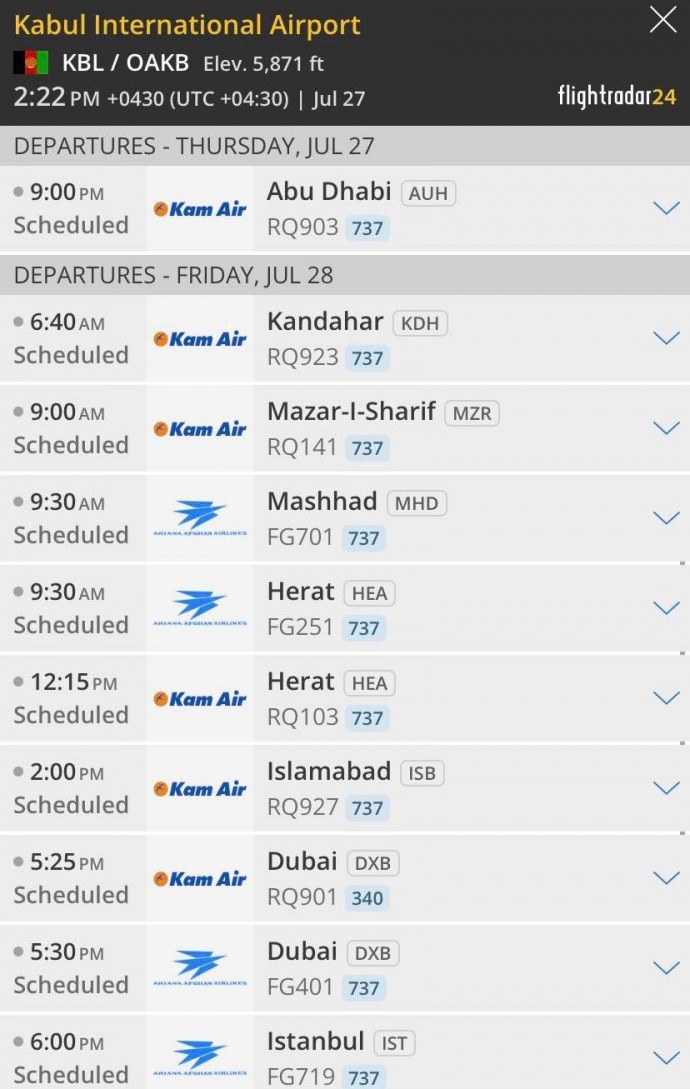

Source: Flightradar

Secondly, according to international rules, airlines are not allowed to operate flights without liability insurance, explains Larysa Nepochatova, the chairperson of the supervisory board of the insurance company Busin. This insurance is not only for passengers, crew, or cargo but also covers potential losses if an aircraft crashes, for example, in the middle of a city.

The EU directive specifies the minimum size of such insurance for airplanes based on their weight. For instance, the possible insurance compensation amount for a Ukrainian AN-24 aircraft is at least 150 million euros, with an additional 50 million euros for military risks. For Boeing aircraft, the minimum insurance coverage is 600 million euros.

Due to the enormous potential risks, insurance companies from about 40 to 50 countries participate in reinsurance to share the liability for insuring even a single aircraft, Nepochatova points out. Therefore, the decision of the Ukrainian authorities to open the airspace, even with the involvement of local insurance companies, is insufficient to cover such significant risks.

Unlocking the Ukrainian airspace is possible with the presence of international guarantees, similar to what was done in the context of the “grain deal.”

“We, as insurers, love documents, not assurances. Even when the situation seems stable in a certain region, no insurer will believe it without proper documentation. So, whether insurers will agree to open the airspace can only be determined when a legal document is in place. This document must guarantee that there will be no direct clashes or missile bombings,” emphasizes Nepochatova.

If an international agreement is reached, insurers will send Ukraine questionnaires, where they will need to specify the risks for airports, airlines, regions, and routes in detail.

The first flights — cargo

In both scenarios, the question remains whether passengers will trust in the safety of the flights and whether Ukraine can convince foreign airlines and international regulators about this.

“If we are talking about passenger transportation, any passenger flights are impossible without a full security conclusion from the Ukrainian Armed Forces and security agencies, which will be confirmed by international civil aviation safety organizations,” emphasizes aviation expert Kyrylo Novikov.

In his opinion, there might be openings for transportation in the form of piloted small aircraft for a limited number of people, but it will not be a revival of the market in the traditional sense. Most likely, the easing of restrictions will start with cargo transportation, such as transporting goods with drones, a method that Nova Poshta once tested.

Why did Ryanair “fly in”?

There are several arguments as to why civil aviation may not be able to operate until the end of the war and immediately after its conclusion. So why go through all these stages of restoration now, and why did Ryanair’s management decide to visit Ukraine?

According to Dolintse, even partial opening of the airspace for civilian aviation will provide an opportunity for Ukrainian airlines to maintain their certificates, preserve the qualifications of their personnel, and generate some minimal income. This applies to both airports and carriers.

At the same time, it seems that the fight for aviation’s operations in post-war Ukraine began with Ryanair’s visit.

“Every carrier will consider that they have to launch flights to Kyiv. It doesn’t matter if it’s profitable or not, it will be a PR move,” said Dmytro Seroukhov, the CEO of the Ukrainian company SkyUp, in an interview with Economichna Pravda.

Ryanair is known for its aggressive development strategies and the displacement of competitors with very low ticket prices. Indeed, the announcements about investing $3 billion and placing 30 new Boeing aircraft in Ukraine after the war appear to be a smart PR move to position themselves to start operations early and capture a larger market share.

When Ryanair entered the Ukrainian market in 2017, the government made concessions and reduced airport fees. Now, history seems to be repeating itself. O’Leary hinted that he expects further reductions in fees from Ukraine.

“We can only fill flights by selling air tickets for 15 euros, 20 euros, 25 euros. That’s why the airport fees here should be very low. The Ministry of Reconstruction should help with this,” he said.

However, reducing airport fees means reducing the profitability of airports.

Ryanair became the first international company to come to Ukraine to negotiate future operations, but according to Novikov, it won’t be the last.

“This confirms the intentions that Ukraine is interesting to the world and the global aviation industry. I expect such visits from top managers of other leading companies that worked in Ukraine before the war,” he says.

Before launching passenger flights, Ukraine still has a lot to do, but the competition for the right to operate in this market has already begun.

Originally posted by Dana Hordiychuk on Economichna Pravda, translated and edited by the UaPosition – Ukrainian news and analytics website

See also: Why is the “Israeli model,” which the USA proposes for Ukraine, impossible?