Table of Contents

Oksana Semenik’s story is about the occupation in Bucha, studies in the USA and millions of views on Twitter.

In early February, the Metropolitan Museum changed the title of Edgar Degas’ painting Russian Dancers to Ukrainian Dancers, as it really is. At the same time, the museum recognized the artists Ilya Repin and Arkhip Kuindzhi as Ukrainians – the first was born in the Kharkiv region, the second in Crimea, and the third in Mariupol, but Russian propaganda for years passed them off as “their own”. One of those who influenced this renaming is Oksana Semenik. She is 25 years old, an art historian and a journalist. In March 2022, Oksana and her fiancé spent two weeks in the basement of Russian-occupied Bucha (the Kyiv region) and then left the city on foot. A few months later, Oksana flew to the United States to research post-Chornobyl art and accidentally saw that many Ukrainian artists in museums there were still signed as Russians. Oksana Semenik launched a campaign to rename them and started an art Twitter account that is followed by hundreds of thousands of people. The world media began to write about her and the decolonization of art. However, the New York Times article shows that Europeans and Americans do not understand why renaming is important, and The Guardian wrote that they did not receive an answer, although, according to Semenik, they did not contact her. Babel’s (Ukrainian news website) correspondent Oksana Rasulova tells the story of Oksana Semenik – about museums, decolonization, Russian curators, the occupation of Bucha, and glitter.

Museums

When Oksana Semenik was four years old, in the summer she went with her mother to Feodosia. Two things impressed her there – the sea and the Aivazovsky National Art Gallery. The gallery was small, so the paintings hung on the walls in several rows. Oksana’s first childhood memories are connected with it: she is standing in this small gallery, and there is a vault with paintings above her, and it does not disturb her but rather calms her down. Then Oksana went to art school, where she always painted the sea. Her mother raised two children on her own, so they rarely traveled. But Kyiv museums were free for children. That’s how Oksana began to explore the world of art.

“As a child, I wanted to know the story behind each painting,” she says.

As an adult, Oksana came to the same Kyiv museums and noticed that she reacted differently to what she saw. The museums taught her to ask herself new questions and hear new answers, showing her the experience of distant and unknown people and countries. Whenever she visited a new city or country, Oksana made it a habit to go to the local museums, so she could learn about the context, culture, and history. She liked to go to a gallery in Krakow, for example, and study how Poland was changing through the paintings.

See also: Decades and billions of dollars. When will Ukrainian fields and cities be cleared of Russian mines?

In 2017, Oksana traveled to the Donetsk and Luhansk regions with the project “Museum Open for Repairs” (a program to reorganize small Ukrainian museums in different regions of the country with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.). Then she realized that museums in small frontline towns could also be important and help work with the experiences of the war. At the end of 2021, Oksana began writing her thesis on post-Chornobyl paintings and moved to Bucha.

Bucha

In Bucha, Oksana used to live in the Glass Factory, as the locals call the residential area near the Bucha Glassworks. In November 2021, Oksana’s boyfriend, a Kyiv-based videographer and photographer Sasha Popenko, moved in with her. Oksana recalls that she really liked it in Bucha. The apartment was spacious and cozy, near a forest and a lake. Life seemed peaceful and safe, so when news broke in November 2021 that the Russians were planning to advance on Kyiv, Oksana was not worried.

“We imagined that bombs would be flying at Kyiv and that Russians would be advancing from Donbas,” she recalls. “Sasha and I were joking: who would go through the Chornobyl zone?”

On February 25, 2022, Oksana’s father was supposed to take them to the village to visit Oksana’s grandmother. But he was unable to leave Kyiv because of the checkpoints. Oksana, Sasha, and their cat Vatrushka first went down to the basement of their five-story building, and then “moved” to the better-equipped basement of a neighboring kindergarten. They spent two weeks there with other Bucha residents. Sasha sometimes went out to take pictures of the neighborhood, Oksana read The Bullfighters from Vasyukovka, took care of the cat, played with the children, thought about what books and articles she would write, and dreamed of going to the Hermitage to return the looted by Russian troops goods.

On the third day in the basement, after she and Sasha had not decided to be evacuated, Oksana asked him with fear what was next. He answered:

– “Well, let’s create a family.

– “Maybe then will you say in a normal way?” she clarified.

– “Will you marry me?” Sasha asked.

Oksana recalls that she joked that she would die engaged, but she kept saying that they would get out. The wedding was planned for Independence Day of Ukraine on August 24. In the basement, they discussed where to celebrate, what kind of dress to wear, who to invite as a photographer, and who would be on the guest list. Meanwhile, real life was becoming more and more unbearable: they saved on food and water, did not bathe, used a bucket to go to the toilet, and slept in their clothes and shoes.

On March 10, the head of the Kyiv Military Administration, Oleksiy Kuleba, announced that a humanitarian corridor would be opened from Bucha for evacuation. Oksana and Sasha decided to leave. They walked in a large convoy, not knowing whether it was safe and where the Zhytomyr highway would lead. Surprised Russians let the convoy pass through checkpoints. In total, Oksana and Sasha walked about 20 kilometers.

“I shed a tear when I saw the Ukrainian military at the checkpoint,” Oksana recalls, and even now she is still glowing at this moment. “I can’t even describe this happiness. I showed my passport, passed through, behind the backs of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and immediately felt safe because no one would kill you just for existing. I just couldn’t believe it.”

After leaving Bucha, Oksana could hear the rumble of tanks, had dreams of the occupation, and was afraid to wake up in the basement. She still tries not to think about her experience too deeply to keep herself going. She says that her experience of the occupation is not so terrible compared to the one in Kherson. She says she would prefer to never remember it – and at the same time, she is terrified of forgetting.

“God forbid we teach our children and grandchildren wrong. They must know all this. That a Russian is an enemy. That he will attack, steal, kill, even if he seems normal. The next generation must not forget, just as we have not forgotten the Holodomor,” says Oksana.

Oksana and Sasha got married in August in Kyiv, where they now live. Everything went almost exactly as they had planned in the basement, except for the date. The wedding was postponed to the beginning of the month because on August 24, Oksana took a train to Poland and flew to the United States.

USA

In April, Oksana received a letter from her former colleague Daria Badior asking if she would like to go to the United States for a few months to do an internship at the Zimmerli Art Museum in New Jersey at Rutgers University where curator Olena Martyniuk is looking for Ukrainian researchers. This museum has the largest collection of art in the West from countries that were once under Soviet occupation. Of course, Oksana would like to.

But she hesitated. At first, they offered to come for three months. Then they were not sure whether they would have funding. Later, they asked Oksana to come for a year. When she read the last letter, she cried. She looked at the map from the museum where she was invited to her childhood dream – the Museum of Modern Art in New York was only an hour and a half away. Before, Oksana would not have even hesitated, but now she did not want to be away from her country and her fiancé for so long. In the end, they agreed that Oksana would come for the fall semester and then decide whether to stay.

In late August, Oksana arrived in Highland Park, New Jersey. The small university town was populated by Jews, Latinos, African Americans, and descendants of Ukrainian immigrants.

“I planned to study post-Chornobyl art,” says Oksana. “I knew about the need for decolonization, but I didn’t plan to do it.”

The university gave her access to the museum’s digital database. Oksana set the time frame and the Ukrainian filter in the search to select works for her research. There were very few paintings. Then she became interested in what was painted about the Chornobyl disaster in Russia. She came across a 1986 work by a “Russian” she didn’t know, Yuriy Semash: an icon of Saint George, an Easter cake, didukh (Ukrainian Christmas decoration, made from a sheaf of wheat), and a candle. “Russians have a didukh?” Oksana was surprised. I googled him: Semash was born and lived in Zaporizhzhia, and he had worked in Moscow for only a few years. It all fits together: the work, dated May 4, a week after the Chornobyl explosion, was one of the first to reflect on the disaster, as people seek God during the apocalypse, even despite Soviet anti-religious censorship.

Oksana wondered how many other Ukrainian names there were in the Russian section. She checked all 900 people, and 70 of them turned out to be Ukrainians, and another 80 were from other countries occupied by Russia.

“I did it quietly,” Oksana says, “and didn’t talk about it until I had processed 40% of the Russian database.”

Oksana made a presentation for two curators of the Russian Art & Soviet Nonconformist Art department, an American Jane Sharp and a Russian woman. Jane was immediately on Oksana’s side – she used to research Russian art but stopped after the full-scale invasion. The Russian woman argued. She called it “ours, Soviet” and said that nationality was no longer relevant, and it was difficult to define it. Oksana disagreed: for a few years they do not turn a Ukrainian artist into a Russian one in Moscow. She said that one does not write about Indian artists “from the British Empire,” just as one does not mention the Third Reich when talking about Germans. She explained that, according to the principle of the borders of that time, one should write about the Ukrainian People’s Republic but they don’t do that. I reminded them that it is wrong and indelicate to call Ukrainian cities Russian when Russian bombs are falling on them. Slowly, but the arguments worked.

Eventually, after some debate and with Jane’s support, a compromise was reached: the “nationality” column would be removed and the place of birth, work, and death would be written instead. However, it takes a long time – all the signatures in the systems need to be changed. So the process is still ongoing.

On her free Fridays, Oksana traveled to New York. She went to the Museum of Modern Art, which she had only dreamed about before. Besides her delight, she felt disappointed: Ukrainian artists Malevich and Ekster were signed as Russian. In the room with Picasso, Gauguin, and Matisse there was not a word about African art, which they were inspired by and called primitive at the same time. In the section about America in the 1960s, they did not write about Vietnam. At the exhibition about Ukraine In Solidarity, there is not a single word about Russia waging war against Ukraine. It was even more surprising that the same Malevich and Ekster in this exposition were Ukrainians after all. Oksana did not see the expected context, discussion, statements, or work on important topics.

From the United States, she continued to do projects in Ukraine. She was often tired. She was seriously ill twice, and her hair began to fall out. The house where Oksana lived was not far from the airport – she woke up to the sound of airplanes and was afraid that war had broken out. In recent weeks, she listened to the song “Cry of the Soul” by Kurgan & Agregat (the Ukrainian hip-hop band from the Kharkiv region) and couldn’t wait to get on a plane to Europe.

“When I said in the museum that I was taking the tickets home, they didn’t believe me,” says Oksana. “There were massive rocket attacks and blackouts, so no one understood me. They thought that I was just an emotional Ukrainian woman who didn’t know what she wanted – and this is also colonial thinking about others.”

Oksana returned to Ukraine happy. She immediately felt better at home. She planned to rest, but she continued to work with Ukrainian media and write to foreign museums about decolonization, both through personal communication in letters and through public questions on Twitter.

Art and Twitter

Back in June, while preparing for a trip to the United States, Oksana started an English-language Twitter account called Ukrainian art history. Firstly, she wanted to have such a channel, and secondly, she needed to practice talking about Ukrainian art to a foreign audience. She started with tweets about Arkhip Kuindzhi, Fedir Krychevsky, and Kateryna Bilokur. Twitter quickly gained 1,000 followers. Now Oksana is followed by more than 17,000 people, and the account has turned into a full-time job of finding stories and works. Foreign media often ask her for commentary on Ukrainian art, and diaspora people send photos of paintings from Ukraine and ask her to identify who painted them or share findings in American archives.

After researching in the United States, Oksana began tagging specific museums to change their captions. Some responded to her personally: for example, the Smithsonian American Art Museum after correspondence with Oksana, added the caption “now Dnipro, Ukraine” to “Yekaterinoslav, Russia” in the story about Helen Gerardia. In total, Oksana found 40 more Ukrainian artists in their database who are listed as Russians, and she is now continuing to negotiate to rename them. She breaks the rules of the academic world and points out the mistakes of the MoMA (the Museum of Modern Art), the Met, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Jewish Museum. Someone is listening: the Met renamed Degas’s Russian Dancers to Ukrainian Dancers and signed Repin as a Ukrainian. And with someone, it’s more difficult.

“The Brooklyn Museum said that it would take them years to do their own research on this topic,” says Oksana.

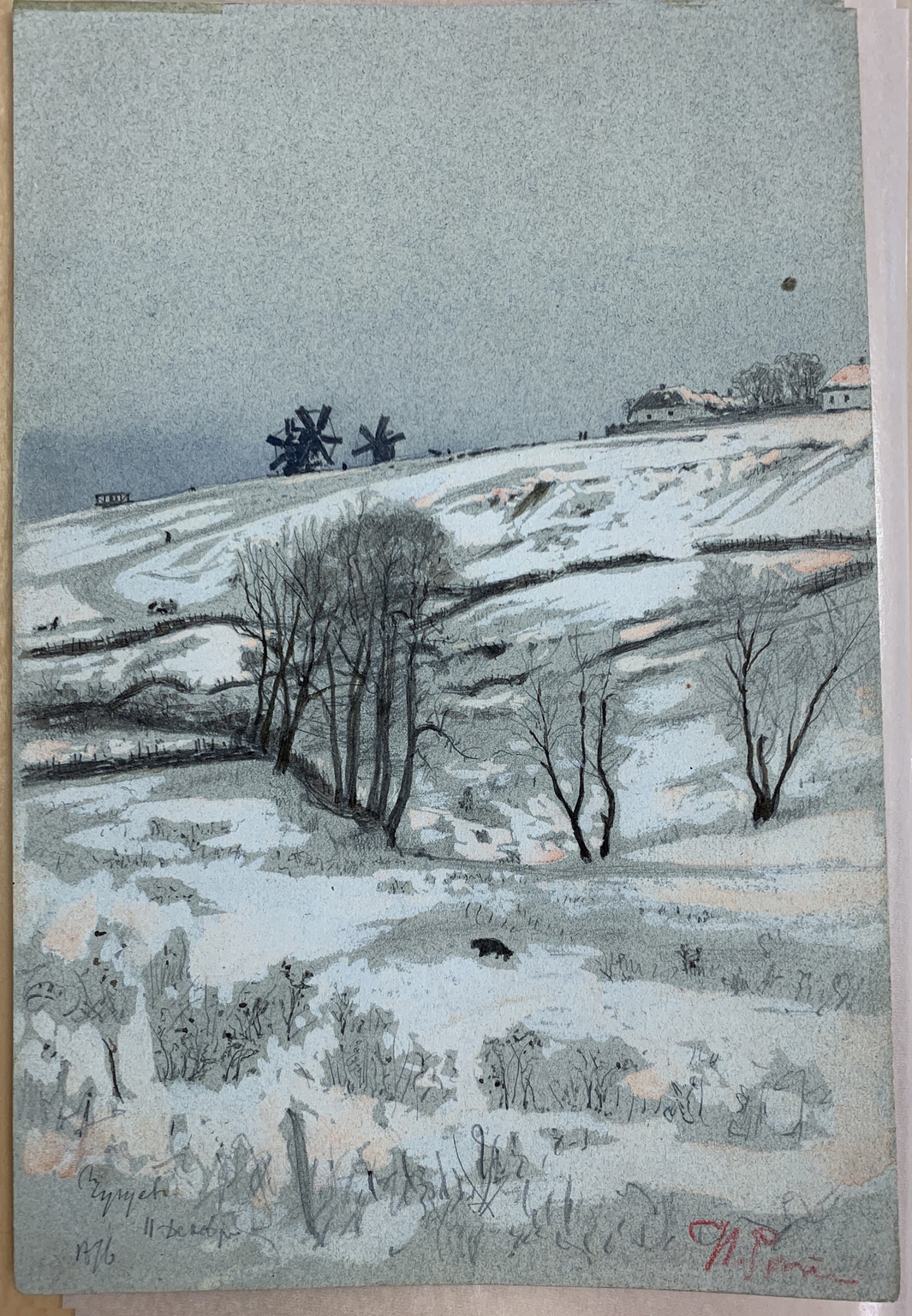

Some of the works are labeled as being about Ukraine, for example, Repin’s Winter Scene, Russia is signed “Chuhuiv,” which is in the Kharkiv region.

So the landscape is not Russian. And Repin himself called Ukraine his homeland. The museum replied that he died in Russia, although in fact it was the occupied Finnish village of Kuokkala, where he deliberately moved away from Russia.

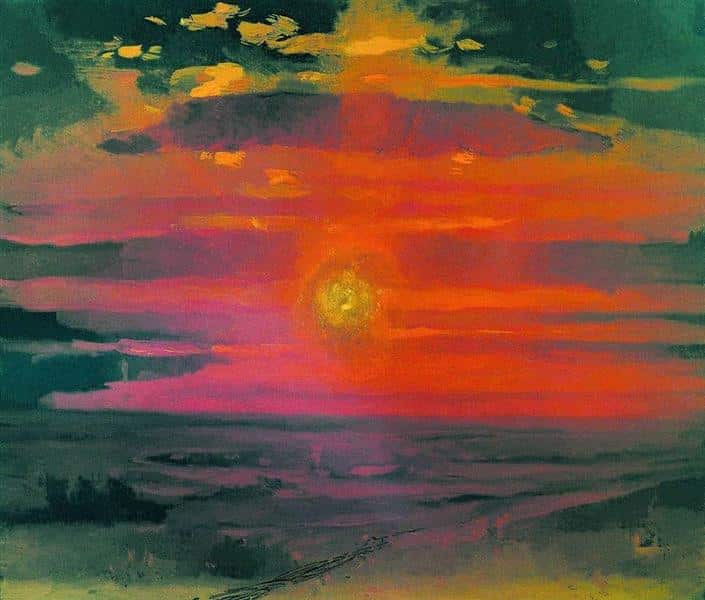

Such explanations take a lot of time and effort. Oksana has to argue with people who should have a keen understanding of contexts, but have succumbed to Russian propaganda. She says that for years Russia has been turning the Ukrainian avant-garde – Malevich, Exter, Burliuk into one of the pillars of its own propaganda. The Bolsheviks claimed that it was their revolution that gave rise to the avant-garde, which spoke of freedom, individuality, and a new order. In fact, the movement was formed before them. And the Soviet government later censored it, throwing its opponents out of galleries and books. At the same time, the avant-garde artists had ties to Ukrainian traditional art and communicated with embroiderers.

Oksana suspects that it’s not just the power of propaganda, but also money – for example, many of Exter’s paintings were donated to the MoMA and Met by a Russian collector. Still, she hopes that public campaigns will work. Just as it happened with Arkhip Kuindzhi – Oleksandra Kovalchuk from the Odesa Art Museum managed to get the Met to write about him not as a Russian, but as an Armenian born in Ukraine, and to note that his museum in Mariupol was destroyed by Russians.

In March Oksana will start working in a large Ukrainian museum to do this more effectively. Then she will be able to speak not just as an activist, but as a representative of an institution, which is essential in the academic world.

“I do this because I am personally angry that Ukrainian artists are underestimated, that Russia kidnaps them and passes them off as their own. And then people think that Russians are cool,” says Oksana. “This affects the fact that in the West they don’t believe that people with such a culture can commit such horrible crimes. But Russian culture is a myth. The real one doesn’t work. Otherwise, there would be no crimes committed by Russians in Ukraine, Chechnya, Georgia, and Syria. Because culture is not only high art, it is also a worldview.”

It is also important for Oksana that people abroad learn about Ukraine, and the signature under Malevich can be a stimulus for this.

“We still have a Soviet perception, but museums are powerful institutions where they conduct research, make statements, reflect, popularize art, and create public space. Oksana explains. I think that in Ukraine, museums can work on the topic of war trauma, for example, and this will unite people,” Oksana explains.

She still tries not to comprehend what she experienced in Bucha because of the pain and fear. She continues to work with a psychotherapist. She admits that she doesn’t believe that all of this – Russian occupation, the United States, and decolonization are really happening to her. But every day, Oksana puts on makeup – and always glitter! The same ones she used to take to the basement in Bucha and imagine that she would put them on herself and others to celebrate the Day of Liberation. Now she says: “Why not shine if we are alive?”

Originally posted by Oksana Rasulova on Babel. Translated and edited by the UaPosition – Ukrainian news and analytics website