Table of Contents

In the coming months, FPV drones, also known as first-person-view drones, where the operator controls the drone through special goggles, could become Russia’s primary response to Ukrainian advantage in modern technology.

No Western weapon supplies can keep up with the speed at which these drones can destroy it. There might even be a real threat of losing the war if Ukraine doesn’t immediately start addressing this issue.

The main point of the article

FPV drones have the highest “efficiency/cost” ratio, and their production can be rapidly scaled up due to their low cost and simple technology. Ironically, Ukrainians introduced their use, but totalitarian Russia is capable of mobilizing resources for production much faster.

Lancet drones which are very serious weapons and have already destroyed several hundred of Ukrainian important targets since the autumn of 2022, pose a lesser threat than FPV drones due to the limited quantity Russia can produce. Shahed drones, whose numbers could increase tenfold after the construction of a plant in Russia, are highly dangerous to static infrastructure objects, but their direct impact on the battlefield is much smaller.

At the same time, FPV drones, if widely disseminated, could become a tool of almost mass destruction: they allow for quick strikes while being relatively safe, cost very little, can inflict substantial damage, and are precise munitions that can even target moving vehicles.

The worst part is that there is currently no ready-made defense solution that can be produced on the same scale and with the same speed as these drones emerge.

According to estimates from open sources, Russia is currently producing no fewer than 11,000 such drones per month (see methodology within the text), which enables it to target about 2,000 objectives — we are using a very conservative estimate of 5-6 drones per target. The best analogy is to imagine 11,000 additional guided projectiles each month, which are also easier to employ.

It seems that the current bottleneck that is holding back their widespread use by Russia is the limited number of operators and reconnaissance teams capable of controlling the drones or identifying targets for them. Consequently, as soon as Russia trains enough military personnel, Ukraine can expect a massive increase in the strikes on equipment and personnel.

And Russia is actively working on this: they have already announced several training programs for operators of such drones, and several training centers are already operational.

What is an FPV drone?

An FPV drone is a type of drone where the operator wears special goggles that display the same view as the camera on the drone. These drones were originally designed for entertainment purposes, such as racing on tracks with challenging obstacles like narrow passages and abandoned buildings. Such a drone can reach speeds of up to 150 km/h and is extremely lightweight.

Many have certainly seen how the Armed Forces of Ukraine use these drones to destroy Russian bunkers, tanks, and vehicles. However, the Russian army is also not standing still; it is learning and trying not to fall behind. Considering Russian enormous financial and production resources, its long land border with China, and its political friendship with that country, Russia’s prospects in developing and mass-producing such drones outweigh those of Ukraine. It’s no secret that both Russia and Ukraine source components for drones from China.

Source: Texty

Why are FPV drones dangerous?

War is, to a large extent, a matter of mathematics. And the most crucial aspect regarding FPV drones is their effectiveness and affordability. Everything they target will be destroyed. Therefore, these drones, no matter how many are produced, are kept as simple as possible, and cost-saving measures are essential. The focus is on maintaining good quality for the main elements: the control board, communication module, and antenna. The average cost of such a drone is a few hundred dollars, while the damage it can inflict may amount to hundreds of thousands or even millions.

Production can also be economized by using soldering instead of connectors and using simple engines with limited resources. The batteries are maximally compact to provide flight times of around 20-30 minutes for a one-way trip. Frames are made from basic materials such as plastic, fiberglass, and sometimes plywood. There is no need to use lightweight carbon frames as they are expensive and challenging to manufacture.

The payload requirements are also not high, just 2-3 kg. A typical “ammunition” for such a drone is a shot from an RPG-7. Depending on the type, such a shot weighs the same 2-3 kg and is suitable for targeting vehicles. With it, one can disable or even destroy a tank, armored personnel carrier, infantry fighting vehicle, or completely incinerate automotive equipment.

However, they also use 60 mm or 82 mm mortar shells, hand grenades, or even makeshift explosive devices made of TNT or plastid — plenty of explosives are available on the front lines.

Moreover, there is information that Russia is already producing unified ammunition for such drones.

Source: Texty

But besides cost, simplicity, accessibility, and a variety of combat payloads, FPV drones also have another significant advantage — precision. An FPV drone is like a self-guided projectile that doesn’t require a launching platform, is much lighter, and hundreds of times cheaper. It can hit a target by flying into a bunker or building through a window while remaining concealed from a distance of 3 km to 8 km. Moreover, it is difficult to identify the launch site of such a drone.

Ukraine began actively using this type of drones in the autumn-winter of 2022-2023, and by mid-summer 2023, the Russian army had already established their mass production and, most importantly, pilot training. Ukraine is also manufacturing them, but it needs more and train pilots on a larger scale.

Piloting an FPV drone is more challenging than a conventional one. Firstly, because of the absence of “assisting tools” on the aircraft itself that stabilize it in the air — there are no numerous sensors and auxiliary modules. The pilot has little time to hit the target — thus, he needs to be skilled at performing tasks quickly.

Moreover, the drone needs to fly in close proximity to the enemy and hit the target, and this requires expertise as well. Of course, electronic warfare can interfere, as well as attempts to shoot down such a drone with rifles or machine guns, so flying quickly is necessary.

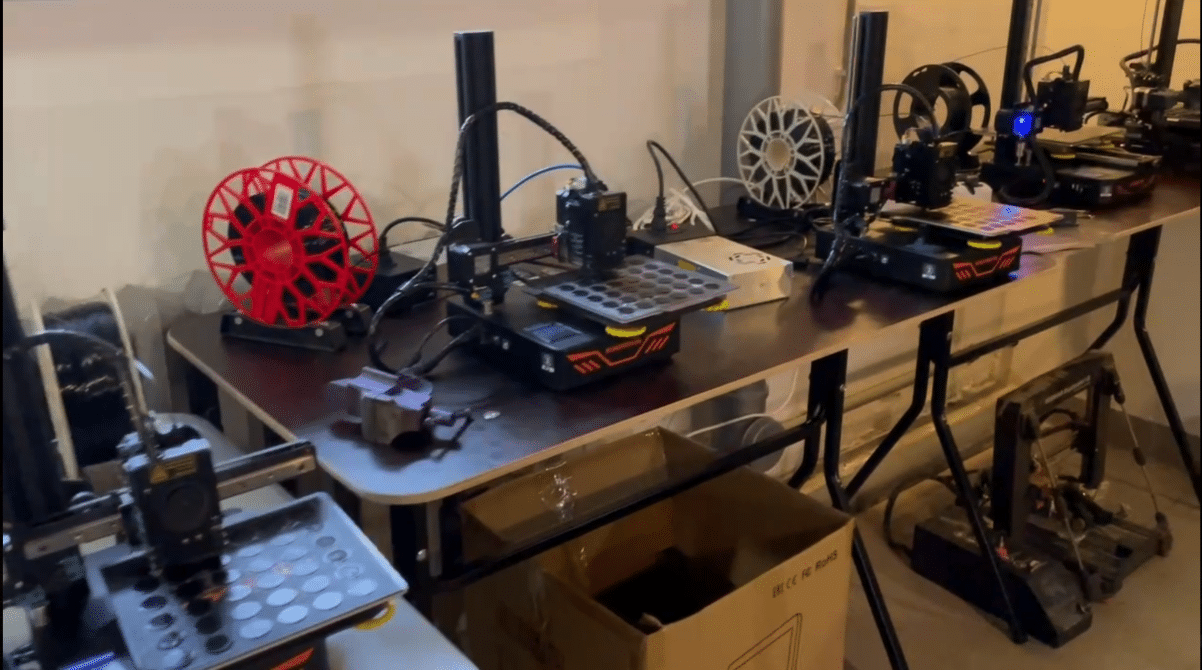

You can manufacture tens of thousands of kamikaze drones, but you still need to train pilots for them, and Russia is actively engaged in this through various regional centers, clubs, and “volunteer” initiatives.

Throughout Russia, pilot training centers have been springing up like mushrooms after the rain.

Maria Berlinska, a veteran of the Russian-Ukrainian war, volunteer, and head of the NGO Aerial Reconnaissance Support Center, estimates Russia’s potential for manufacturing FPV drones at around 40,000 to 50,000 per month.

Our assessment based on open-source data provides roughly similar figures, although possibly slightly more modest.

From open sources, it is evident that the Russians are manufacturing 11,000 FPV drones per month — and it is likely that their production will continue to increase.

Texty (media outlet) has investigated 19 groups for which information is available in the public domain, indicating that they are producing these drones for Russia, and we have calculated that just these groups alone could manufacture up to 11,000 drones in a month. Among them are both state-owned factories and volunteer groups.

Source: Texty

This estimate is approximate, and it was determined using a conservative scenario — we have not accounted for all initiatives. Both the Russian and Ukrainian armies are establishing FPV drone production directly at the frontlines, at the 2nd or 3rd lines, at the battalion and brigade levels. However, we had the opportunity to investigate only public initiatives.

We can assume that Russia allocates significant funding for the production of these drones and is not concerned about the profit margins earned by manufacturers or the transparency of their working schemes — the main focus is on quickly establishing production and supply. This also applies to training centers.

As we have already mentioned, with this quantity of drones, it is possible to target at least 2000 objectives per month. These targets can vary greatly, from individual Ukrainian soldiers, bunkers, and mortar or artillery crews to multiple rocket launch systems or radars.

This weapon indeed poses a huge threat and can become a serious problem.

Strengths of using FPV drones

Cost-effectiveness and mass production. As mentioned before, the affordability of production has already been highlighted. These drones can be easily manufactured using components from the civilian market, and the technology is simple enough for multiple manufacturers to utilize simultaneously.

See also: Lancets: How Russia manufactures kamikaze drones despite sanctions

No need for coordination. Another advantage is the absence of the need to coordinate actions with other units. For instance, using mortar teams or artillery batteries requires coordination with the company commander — platoons do not have such authority. For using artillery, typically a battalion commander’s directive is necessary. However, FPV drones can be autonomously used by squads, platoons, and companies. Speed on the battlefield contributes to success.

FPV drones can track moving targets. FPV drones have the capability to pursue and track mobile targets.

Relatively high power. As mentioned, a popular payload for these drones is RPG-7 rounds, which are prevalent in both Russian and Ukrainian armies. These rounds can damage tanks or destroy MT-LBs, cars, or bunkers. They have a relatively low rate of misfires and do not require additional activators (the RPG round explodes upon impact).

Accuracy. The drone is fully controlled, unlike a mine or projectile. It can even track moving targets.

Specifics

However, drones have their own specific characteristics compared to other types of weapons.

Logistics. Drone logistics are much simpler than, for example, artillery shells. They are lighter, although more delicate, and take up a lot of space. However, they can be easily transported in regular vehicles, carried on foot, or loaded onto carts. While it may not be possible to transport large quantities of drones, there are no significant difficulties in this regard.

However, there is another side to the issue. In authoritarian Russia, the free distribution of weapons is not supported. The respective “workshops” and “volunteers” deliver unarmed drones to the military, and the units equip them themselves — adding an unnecessary step and complicating the process. Additionally, there is a possibility of influencing the enemy by spreading the idea that this ideal weapon could be used inside Russia in case of internal conflicts.

High cost of pilot training. Unlike artillery or mortars, there is little teamwork and no “adjustment tables” involved in operating drones. The accuracy of a drone’s strike depends solely on the pilot’s skill and reaction speed. Training such a pilot is challenging, and not everyone is suitable for this role. Consequently, these pilots and their units are highly valued and are priority targets for the enemy.

Low reliability. Despite mass production, FPV drones are manually assembled, which leads to defects. The quality of these components is also variable, often sourced from “Chinese” manufacturers. As a result, drones can crash or malfunction due to individual module failures, such as motors. Moreover, although the principles of using all FPV drones are similar, they still differ depending on the manufacturer, making a seamless transition from one model to another challenging.

Source: BPLAROSTOV

Ways of countering and weaknesses

The Ukrainian state, in cooperation with volunteers and its own factories, has made significant efforts to develop drones.

However, the state needs to be more agile and respond faster to emerging battlefield situations. We see that FPV drones currently do not receive enough attention, despite their potential to become a significant factor in victory or defeat.

Although these drones are actively produced in Ukraine.

Consequently, pilot training and drone production should become more widespread. Organizations involved in drone manufacturing should receive financial support, and it does not matter how much profit these companies make — what matters is that there are drones. To achieve this, efforts should be made to change the legal framework for allocating funds, so that anti-corruption agencies do not burden manufacturers with criminal cases later on.

Maximally simplified import procedures are needed. The state should facilitate the export of spare parts from other countries since there is a real economic war over drone components.

The Ukrainian diplomacy should exert pressure on other countries to prevent Russia from importing microelectronics and UAV components, and advocate for sanctions and penalties for violations of sanctions, even from China’s side.

In addition to the production of FPV drones, more attention and resources should be devoted to their defense.

We do not have a definitive answer on the most effective method — most likely, a combination of approaches will be needed. Below are very approximate ideas within the framework of initial brainstorming:

- Reducing Russia’s production. The General Staff and the Security Service of Ukraine should systematically destroy FPV production facilities both in the occupied territories and deep inside Russia. Engineers involved in the production and related technologies should be targeted for elimination.

- Strengthened efforts against “reusable” drones that provide targets for disposable FPV drones.

- A combination of electronic warfare (EW) assets to locate operators and artillery to strike them. It should be a counter-operator war, similar to counter-battery warfare.

- Development of specialized anti-drone rifles capable of disrupting the analog control channels of FPV drones. Radio interference is less effective against analog drones, and standard anti-drone rifles do not work in this case.

- Automatic detectors + devices installed on vehicles that will jam the required frequency ranges. The goal is not necessarily to neutralize but to reduce the control and accuracy of the drones. Similar developments exist in Israel, but they are unlikely to sell them to Ukraine. Even if by some miracle they agreed to sell, setting up mass production quickly would still be difficult. Ukrainian developments are starting to emerge, but besides having individual prototypes, Ukraine needs to put everything that works into mass production. Active involvement of the state is necessary for this.

- Using nets to protect static objects.

- New positions in units. Their task is to detect approaching drones using sensors (and visually) and destroy them with available weapons or at least provide timely warnings to allow personnel to survive.

Texty has come across reports that some soldiers use pump-action shotguns to shoot down FPV drones during their approach. Pump-action shotguns fire pellets, so they have a larger area of effect than rifles and are quicker to reload than shotguns. However, this is more of an idea than a verified practice.

Furthermore, the military command should regularly organize horizontal exchange of expertise — conducting small two or three-day meetings for representatives of different units working in modern warfare areas (EW, drones), involving manufacturers and their engineers.

Civil society must push the state to pay attention to this problem because resolving it requires resources much larger than those available to individual volunteer groups.

We consider it necessary to immediately establish a working group (with full support at the highest level) that will analyze the existing experience in the use and counteraction of such drones, identify the best directions for resistance, and initiate the mass implementation of these methods in the Armed Forces.

There is very little time left before Russia’s significantly larger use of FPV drones — only a few months. If hundreds of new operators and teams are prepared by autumn, it could lead to catastrophic losses on the Ukrainian side, even considering the current production rate of FPV drones in Russia (which is expected to increase).

If we are currently misjudging and greatly exaggerating the threat, potential losses could be so significant that it is better to start addressing this problem immediately.

Originally posted by Denys Hubashov and Anatoliy Bondarenko on Texty.org.ua. Translated and edited by the UaPosition – Ukrainian news and analytics website

See also: Drone warfare: what kind of kamikaze drones are used by Ukraine and Russia?